Digital Twin: Mapping the Invisible City Beneath Busan

As Busan accelerates urban development, its underground remains unmapped, unmanaged, and dangerously opaque. A digital twin could transform that blind spot into a strategic asset for safety, planning, and public trust.

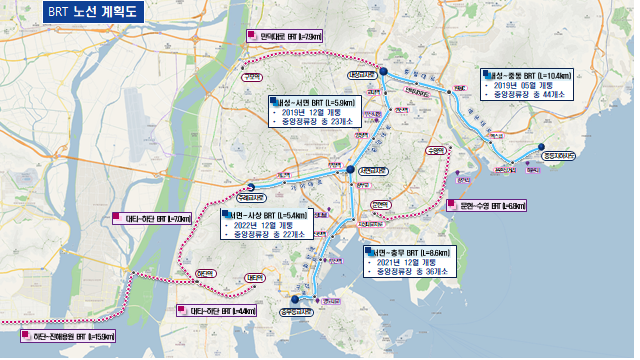

Busan, South Korea — In this fast-growing coastal metropolis, what lies beneath may soon matter more than what rises above. As Busan pushes forward with ambitious development initiatives — from large-scale urban redevelopment to the planned construction of the BuTX underground express rail — the city's subsurface is becoming increasingly congested with critical infrastructure. Subway tunnels, water mains, sewer lines, electrical conduits, and fiber-optic cables now compete for limited underground space, often without comprehensive coordination or oversight.

Despite the mounting complexity of its underground landscape, Busan still lacks a comprehensive, accurate, and publicly accessible map of its buried assets. This absence is more than a bureaucratic gap — it represents a growing public safety liability. Sinkholes continue to appear. Undetected leaks quietly erode soil beneath busy roads. Construction mishaps cause disruptions to essential services. Although the city has conducted ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys and maintains fragmented geospatial datasets, the lack of a unified, digital model leaves urban planners, engineers, and citizens alike operating without a clear view of what lies below.

If Busan is to build forward — safely, efficiently, and transparently — it must begin by seeing clearly beneath its own feet.

Busan is building fast — and it is preparing to build even faster. Major subsurface infrastructure projects are on the horizon, including the BuTX deep express rail, the Hadan–Noksan Line, and the undergrounding of the Gyeongbu railway line. While these projects remain in the planning stages, they represent a coming wave of deep excavation that will cut through an already congested and fragile underground environment.

But there are already warning signs. The ongoing construction of the Hadan–Sasang Line has experienced frequent setbacks due to sinkholes and ground collapses, repeatedly delaying completion. Despite years of construction, new sinkholes continue to emerge along the route — a clear indicator that the geotechnical risks were either underestimated or poorly managed.

These failures are not isolated engineering mishaps; they are symptoms of a deeper issue: Busan lacks a unified, accurate, and accessible underground map. Infrastructure owners — public and private — maintain disconnected datasets. Older utilities often have incomplete or inaccurate records. Excavation frequently proceeds with only partial knowledge of what lies below.

As Busan prepares for more complex, large-scale underground projects, this knowledge gap is not only costly — it is dangerous. Without comprehensive visibility, even the best-engineered projects are vulnerable to unexpected disruptions, costly delays, and public safety hazards.

While cities like Busan struggle with fragmented underground data and limited visibility, others have already embraced a fundamentally different approach: integrated, predictive, and transparent underground management through digital twins.

A standout example is Singapore’s “Virtual Singapore” initiative — widely recognized as one of the most advanced national-scale digital twin projects in the world. Developed by the Singapore Land Authority and supported by Dassault Systèmes, Virtual Singapore creates a dynamic 3D model of the city-state that includes not only buildings, roads, and land parcels, but also subsurface infrastructure such as water lines, power cables, sewer systems, and transport tunnels.

This platform is not a static visualization. It is a data-driven, real-time decision-support tool used for urban planning, disaster simulation, environmental modeling, and infrastructure coordination. Before any major construction project proceeds, developers and planners are required to reference this digital twin to assess conflicts, risks, and geotechnical factors. Moreover, the platform is accessible — under license — to public agencies, researchers, and private firms, ensuring cross-sector transparency and collaboration.

By contrast, cities without such infrastructure often rely on legacy maps, institutional memory, or ad hoc surveys. This not only increases the risk of error but also weakens accountability and slows down response when things go wrong. Singapore’s approach proves that it is not only possible but necessary to treat underground infrastructure as part of a living, digital ecosystem — not a forgotten tangle of pipes and cables.

Busan is standing at a pivotal moment in its urban development. With multiple large-scale underground projects on the horizon — including the BuTX deep express rail, the Gyeongbu Line undergrounding, and ongoing subway expansions — the city is preparing to transform not only its skyline, but its subsoil as well. Yet this transformation risks being built on uncertainty if the current lack of underground visibility is not addressed.

What Busan needs is a comprehensive digital twin of its underground infrastructure — a living, three-dimensional model that can consolidate what the city already knows, and reveal what it doesn’t. This system would go far beyond static maps or siloed utility schematics. It would integrate geospatial data from ground-penetrating radar surveys, historical utility line records, and geotechnical assessments into a single, unified platform. Over time, it could evolve to incorporate real-time monitoring through embedded sensors — measuring pressure, detecting moisture, or even capturing subtle shifts in the ground — to anticipate failures before they occur.

But the power of a digital twin lies not just in its technology, but in how it is embedded within the city’s governance. For it to function as a tool for safety, planning, and transparency, it must be recognized as authoritative within urban decision-making processes. This means ensuring that public agencies, private developers, and infrastructure operators all contribute to and consult the model. It also means giving residents a clear window into the underground risks and construction activities that affect their daily lives — not as abstract threats, but as clearly visualized information they can understand and act upon.

By adopting a digital twin, Busan would be taking a critical step toward transforming its underground from a source of confusion and hazard into a managed, predictable, and ultimately strategic layer of the city. In a future shaped by smart infrastructure and resilience planning, the ability to see below will be just as important as the ability to build above.

In the age of smart cities, it is no longer acceptable for urban development to proceed blind to what lies beneath. As Busan expands upward and outward, it must also learn to see downward — with clarity, precision, and intention. The risks of inaction are already visible: sinkholes that swallow roads, delays that disrupt entire neighborhoods, and infrastructures that are built — and rebuilt — in costly, reactive cycles. These are not isolated failures of engineering. They are systemic consequences of planning without full knowledge of the ground we build on.

A digital twin of Busan’s underground would not only improve safety and efficiency — it would mark a shift in civic philosophy. It would affirm that transparency is not a threat, but a safeguard; that informed planning begins with shared knowledge; and that modern cities must be legible to those who live in them, not just to those who build them.

If Busan is to lead as a forward-thinking coastal metropolis — resilient, connected, and accountable — then it must begin by illuminating its foundations.

Because no city can truly rise, until it learns how to see beneath its own feet.

Comments ()