Busan, South Korea – In a landmark step toward greater regional autonomy, the cities of Busan and the neighboring province of Gyeongsangnam-do (Gyeongnam) unveiled a preliminary blueprint on November 8 for a proposed administrative integration. This initiative aims to transform Busan and Gyeongnam into a cohesive “regional economic capital” with expanded local control over finances, legislation, and public services. For South Korea, where administrative authority is highly centralized, the proposal represents a significant shift toward decentralization—an approach gaining traction in various countries worldwide.

Busan and Gyeongnam are among South Korea’s most economically dynamic areas. Busan, the country’s second-largest city and a major international port, is a central hub of commerce and logistics. Meanwhile, Gyeongnam, home to vibrant industrial sectors, is an economic powerhouse with a strong manufacturing base. Together, the regions aim to build on their geographic and economic alignment to foster robust, long-term growth.

This integration effort reflects broader goals within South Korea to address regional disparities and empower areas outside the Seoul metropolitan region. For Busan and Gyeongnam, achieving greater local autonomy represents an opportunity to enhance their status within the national economy while positioning the region as a gateway to global markets.

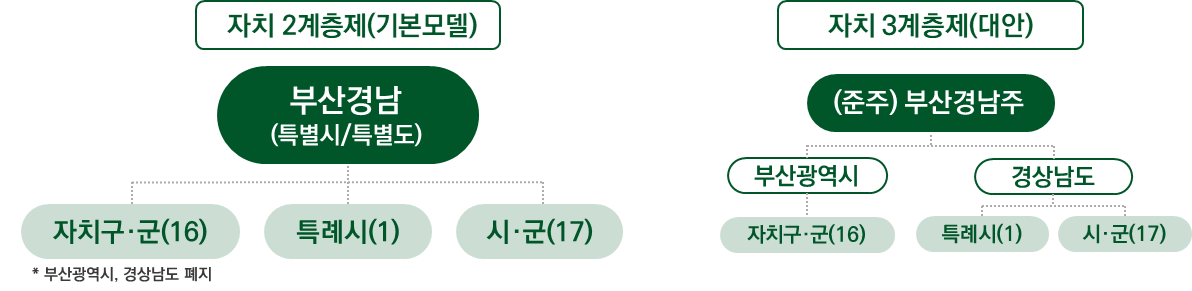

The proposal, titled the “Busan-Gyeongnam Administrative Integration Blueprint,” outlines a vision for stronger local governance with an emphasis on economic development and self-sufficiency. At its core, the blueprint presents two potential models for integration, each with distinct governance structures:

- Two-Tier Model: This streamlined approach would consolidate Busan and Gyeongnam into a unified regional government while maintaining existing local entities. The aim is to simplify governance, allowing the integrated region to make swift, effective decisions and to allocate resources more efficiently.

- Three-Tier Model: Offering a more complex structure, this model proposes retaining the current administrative units while adding a new “quasi-federal” layer of government. This top-level body would oversee strategic functions, granting the integrated region a level of autonomy comparable to federal systems. This structure would allow Busan-Gyeongnam to handle large-scale initiatives while letting local administrations focus on daily management.

The choice between these models will be determined after an extensive period of public consultation and expert analysis, ensuring that the final plan aligns with local needs and preferences.

The integration blueprint seeks to establish a self-sustaining region with increased control over key areas like public safety, education, welfare, and economic policy. By decentralizing these functions, Busan and Gyeongnam aim to attract investment, foster job creation, and enhance service quality, creating a resilient and competitive economy.

Globally, this push for regional autonomy mirrors movements in Catalonia (Spain), Scotland (United Kingdom), and Quebec (Canada), where calls for self-governance reflect both economic aspirations and cultural identity. If the Busan-Gyeongnam model proves successful, it could become a reference point for other regions worldwide that are pursuing greater autonomy to address unique local challenges.

Busan Mayor Park Hyeong-joon, speaking at the unveiling ceremony, described the proposal as a transformative step for South Korea’s regional development strategy. “This is our attempt to reshape the balance of national development from the ground up,” Park stated. He emphasized that the blueprint aims to equip Busan and Gyeongnam with “federal-like authority” to manage their own resources, reflecting a shift toward self-determination within South Korea’s governance framework.

The integration plan, still in its early stages, will undergo a rigorous public review process in which residents and stakeholders will have the opportunity to offer feedback. This approach underscores the administration’s commitment to democratic engagement and helps ensure the proposal resonates with the region’s citizens.

As with any substantial structural change, integrating Busan and Gyeongnam under a single administrative framework will require careful planning and significant resources. Implementing a new governance model involves logistical complexities that could demand considerable funding and adjustment time. Additionally, some officials and citizens may be concerned about potential disruptions to local services or the dilution of existing administrative structures.

Balancing regional ambitions with national oversight will also pose challenges. Decentralization efforts often require careful negotiation with central authorities, especially around issues of funding, jurisdiction, and shared governance. Securing widespread support and successfully navigating these potential obstacles will be essential for the long-term viability of the integration.

The Busan-Gyeongnam blueprint could serve as a model for other regions in South Korea. With longstanding regional disparities remaining a point of focus, successful integration here could encourage other provinces and cities to pursue similar initiatives. If effective, the blueprint could catalyze a new approach to national development, with a stronger emphasis on localized governance and economic self-determination.

This shift toward regional self-governance could mark a pivotal moment in South Korea’s growth strategy, offering new insights into how regions can manage their resources and address local priorities without relying on central government oversight.

If successfully implemented, the Busan-Gyeongnam integration could transform the region into a beacon of economic and administrative self-sufficiency within South Korea. More broadly, this ambitious vision may offer a blueprint for other regions considering greater autonomy, sparking new conversations about governance, economic resilience, and regional identity on the global stage.