Why Busan’s Ballpark Belongs on the Waterfront

As the Sajik Baseball Stadium redevelopment stalls, a bold alternative is reemerging: a world-class waterfront stadium in North Port. But this isn’t just about baseball — it’s about reimagining Busan’s urban identity, economy, and global image.

Busan, South Korea — For decades, Sajik Baseball Stadium has stood not only as the home of the Lotte Giants, but as a cultural landmark deeply embedded in Busan’s identity. Generations of fans have filled its stands, their chants echoing through the city's hills each summer. But now, as the stadium ages and the city's development ambitions grow, Sajik finds itself at a crossroads — and perhaps, so does Busan itself.

Earlier this year, Busan’s plan to reconstruct Sajik Stadium was rejected by the Ministry of the Interior and Safety’s fiscal review, citing concerns over national funding and long-term feasibility. The project, projected at more than ₩320 billion, aimed to transform Sajik into a modern sports and cultural complex by 2031. But with its future uncertain, an older idea is resurfacing with renewed energy: building a new stadium on Busan’s North Port waterfront.

The proposal isn’t just about relocating baseball. It’s about reimagining Busan’s urban future. A North Port stadium — with sweeping ocean views and proximity to cultural landmarks like the under-construction Busan Opera House — could become a bold new anchor for downtown revitalization, tourism, and global attention.

Now, as a snap presidential election looms, and urban strategy takes center stage, the question isn’t only where Busan will build its next stadium. It’s what kind of city it wants to be.

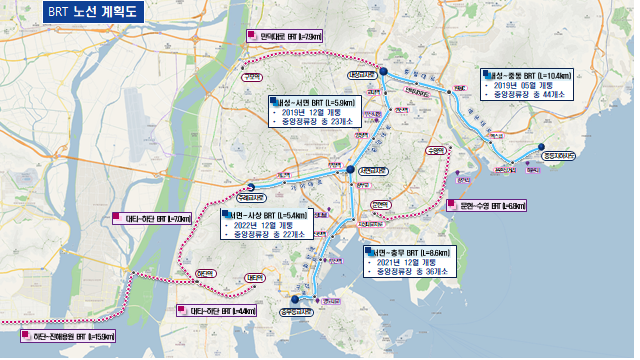

The idea of an ocean-view stadium at North Port is not new — it has surfaced in past discussions, only to fade under the weight of cost concerns and political hesitation. But the recent stalling of the Sajik redevelopment plan, combined with the momentum of North Port’s ongoing transformation, has brought the idea back with renewed legitimacy. Supporters argue that the stadium could serve as a cornerstone for Busan’s downtown revival, anchoring the North Port redevelopment zone with a bold cultural landmark. With sweeping views of the sea and adjacency to major infrastructure investments — including the Busan Opera House, waterfront parks, and planned transit links — a North Port stadium could redefine the city’s global image.

At a time when Busan is vying to assert itself as a premier destination for tourism, culture, and sports in Asia, the stakes go beyond baseball. This is not just about building a new home for the Lotte Giants — it’s about positioning Busan for a post-industrial future, one in which iconic public spaces drive urban growth, attract young residents, and keep the city competitive in a rapidly centralizing nation.

Sajik vs. North Port — Two Visions, Two Futures

Sajik Baseball Stadium is etched into the city’s memory. Opened in 1985, it has hosted decades of triumphs, heartbreaks, and summer nights packed with Lotte Giants fans. Its central location, close ties to tradition, and long-standing community role make it an emotionally resonant space. The city’s plan to redevelop Sajik honors this legacy — promising a modernized, family-friendly venue with upgraded facilities, community spaces, and year-round programming. But the vision, while respectful, is also cautious. It focuses inward, reinforcing what already exists rather than reimagining what could be.

By contrast, the North Port proposal is unapologetically ambitious. Situated at the edge of Busan’s rapidly transforming waterfront, the idea is to build more than a stadium — to create a landmark. With views of the ocean, proximity to the Busan Opera House, and integration into a larger cultural and commercial redevelopment, the North Port site could offer a new urban icon for the city, much like San Francisco’s Oracle Park or Yokohama’s Bay Quarter.

Yet, the two proposals are not merely geographic alternatives. They reflect competing philosophies of urban development.

Sajik prioritizes continuity, cost management, and renovation within familiar boundaries. North Port represents rupture — a chance to leap forward with a globally marketable, visually stunning venue that ties Busan’s baseball identity to its maritime future.

Still, the North Port plan faces serious headwinds: the site is owned by the Busan Port Authority, the land is expensive, and the redevelopment would likely require complex political coordination, not to mention billions in funding. Sajik, for all its limitations, is the safer bet — administratively streamlined, emotionally familiar, and already in motion.

But safety and vision rarely coexist.

Economics, Politics, and Public Imagination

At first glance, the debate between Sajik’s renovation and North Port’s reinvention may seem like a matter of location or budget. But the deeper question is one of urban ambition — and how much Busan is willing to invest in its own future.

The Sajik project, while thoughtfully designed, carries limited economic ripple effects. It modernizes an aging asset, improves fan experiences, and creates modest construction jobs. But its impact remains largely confined to the neighborhood — not the broader urban economy. In contrast, a stadium in North Port could serve as an anchor for waterfront redevelopment, catalyzing tourism, retail, hospitality, and cultural activities along one of Busan’s most underutilized coastlines.

Politically, the North Port proposal has another advantage: it tells a bigger story.

At a time when regional cities are competing to retain population and attract national attention, a bold project like an ocean-view stadium could reposition Busan as a leader in creative urban transformation — one that aligns infrastructure with identity. As cities from Incheon to Gwangju push mega-projects tied to K-pop arenas, art clusters, or green tech zones, Busan’s offer must be equally distinct. Baseball — the city’s most beloved sport — and the ocean — its most powerful symbol — might be the narrative it needs.

This is especially relevant in 2025, with a snap presidential election looming. Major public projects often gain momentum when they are attached to national campaigns, especially those that signal regional investment or economic justice. If candidates begin to court votes in Busan with concrete pledges — not just about decentralization or infrastructure, but about landmark urban renewal — the North Port baseball stadium could become a compelling flagship promise.

And public sentiment may be ready. Online forums, citizen petitions, and fan communities have already begun to revive the idea, pointing to international examples like San Francisco’s Oracle Park, which turned a derelict dock into one of baseball’s most iconic venues. The comparison isn’t just aesthetic — it’s strategic. Cities are not just built with money. They are built with stories that people want to be part of.

In that sense, the real question isn’t: “Can Busan afford to build this stadium?”

It may be: “Can Busan afford not to?”

A Chance to Redefine Busan’s Urban Future

The debate between Sajik’s renewal and North Port’s reinvention is not simply about sports infrastructure. It is a referendum on Busan’s priorities — on what kind of city it wants to be, and for whom.

Sajik’s redevelopment is safe, familiar, and achievable. It preserves legacy and honors tradition. But in a city wrestling with demographic decline, economic stagnation, and uneven spatial development, safe may no longer be enough.

North Port, by contrast, is riskier — but potentially transformational. A stadium there would not just host games; it would activate a dormant waterfront, attract global attention, and offer a new narrative for a city ready to evolve. It would say: Busan is not just preserving its past — it is building its future.

And that future depends on more than blueprints. It requires political will, public imagination, and policy coordination. It demands that leaders think not in election cycles, but in urban generations. That they stop asking whether this stadium is “feasible,” and instead ask whether it is worth it — for the city, for its people, for the decades to come.

Busan has a rare opportunity to do what few cities in Korea have done: to design a landmark that is not just iconic, but catalytic. A place that is not only photographed, but lived in. A project that connects not just physical sites, but civic hopes.

It may begin with baseball. But it must end with belonging.

Comments ()