The James Webb Space Telescope (Webb) has discovered that TRAPPIST-1b, a rocky exoplanet in the TRAPPIST-1 star system, most likely lacks an atmosphere, making it less likely to host life. Although this finding dampens the prospects of life on TRAPPIST-1b, six other Earth-like exoplanets in the system are still waiting to be studied, promising more exciting discoveries in the future.

Using Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), astronomers led by Thomas Greene, an astrophysicist in the Space Science and Astrobiology Division at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California, measured the temperature of TRAPPIST-1b. The exoplanet is approximately 1.4 times larger than Earth and orbits closest to its parent star, a type of star known as an M dwarf or red dwarf. M dwarfs are the smallest stars capable of burning hydrogen in their cores and make up the majority of stars in the Milky Way.

The measurements revealed that TRAPPIST-1b’s daytime temperature is a scorching 446°F (230°C), which is considered too high to sustain an atmosphere. This finding was disappointing for Greene, who had hoped for a denser atmosphere on the exoplanet.

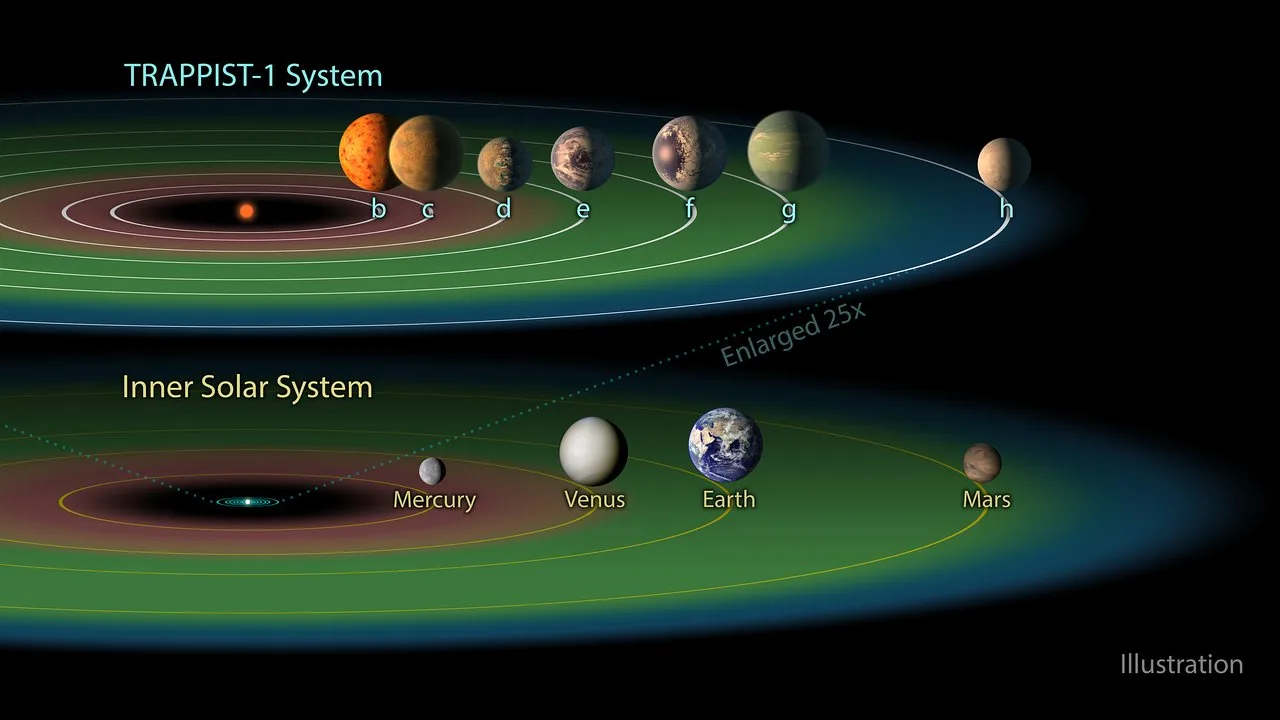

TRAPPIST-1b is situated much closer to its star than Earth is to the sun, with a distance between them only about one hundredth of the sun-Earth distance. Despite its parent star being much dimmer than the sun, TRAPPIST-1b receives approximately four times as much starlight as Earth does from the sun. Prior to ruling out the presence of an atmosphere, astronomers did not expect the planet to be habitable due to its close proximity to the star. Nonetheless, Webb’s ability to directly gather information on such distant Earth-like worlds is a significant breakthrough.

The TRAPPIST-1 star system, located 40 light-years away from the sun, has three planets—TRAPPIST-1e, 1f, and 1g—that could support liquid water on their surfaces and potentially host life. The system is an essential testbed for understanding where the best conditions for life may exist. Furthermore, studying the TRAPPIST-1 system can help astronomers gain valuable insights into Earth-sized rocky planets orbiting M dwarfs.

M dwarfs are ten times more common in the Milky Way than sun-like stars and are twice as likely to have rocky, Earth-sized planets. Greene explains that around 95% of the Earth-sized rocky planets in the Milky Way have stars like TRAPPIST-1 and not like the sun. This fact makes the TRAPPIST-1 system an important focal point for exoplanet research and a key target for scientists looking to explore habitable environments beyond our solar system.

Previous observations using the Hubble Space Telescope and the now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope found no traces of atmospheres on any of the TRAPPIST-1 planets. However, Greene suggests that a very thin atmosphere may still surround TRAPPIST-1b, one that might be completely different from the atmospheres found in our solar system.

The James Webb Space Telescope’s recent findings mark a significant milestone in the study of rocky exoplanets in our own solar system and beyond. The successful temperature measurement of TRAPPIST-1b using Webb’s MIRI demonstrates the telescope’s unparalleled sensitivity and capability to detect dim mid-infrared light emitted by rocky exoplanets.

The TRAPPIST-1 system has become a popular target for exoplanet research due to its unique characteristics and its status as the best-explored planetary system outside our solar system. The seven rocky planets orbiting the ultracool red dwarf star have a similar size and mass to the inner planets of our solar system. Although they orbit much closer to their star than any of our planets orbit the sun, they receive comparable amounts of energy from their tiny star.

The study of the TRAPPIST-1 system, particularly its potentially habitable planets, will continue as astronomers use Webb and other advanced telescopes to examine their atmospheres and gather more data. Elsa Ducrot from CEA in France, a co-author on the paper, highlights the importance of characterizing terrestrial planets around smaller, cooler stars to understand habitability around M stars, making the TRAPPIST-1 system an invaluable laboratory for this purpose.

In conclusion, the discovery that TRAPPIST-1b most likely lacks an atmosphere has broad implications for our understanding of habitable environments around M dwarf stars. While the search for life on TRAPPIST-1b may have been dampened, the remaining six Earth-like exoplanets in the TRAPPIST-1 system hold great promise for future discoveries. The James Webb Space Telescope’s remarkable capabilities will play a crucial role in unveiling the mysteries of these distant worlds, taking us one step closer to finding habitable planets and potentially life beyond our solar system