How Busan Is Using Distributed Energy to Power a New Industrial Era in Gangseo

As a finalist for Korea’s first Distributed Energy Specialized Area, Busan’s Gangseo District is testing new energy models—including battery storage, virtual net metering, and UPS-as-a-Service—to build a resilient, decentralized urban power system.

Busan, South Korea — In the era of digital infrastructure, energy has become more than a utility—it's a prerequisite for industrial survival and competitiveness. From hyperscale data centers to electrified ports and logistics hubs, uninterrupted and scalable power is now fundamental to how cities grow, attract investment, and support innovation.

In May 2025, Busan’s Gangseo District was selected as a final candidate to become South Korea’s first Distributed Energy Resource (DER) Special Zone, a national pilot intended to reimagine how energy is generated, stored, and consumed at the local level. The city aims to move beyond traditional grid-based supply by developing a large-scale battery storage system and launching service-based power models, such as virtual net metering and UPS-as-a-Service.

Behind Busan’s Energy Numbers

At first glance, Busan appears to be one of South Korea’s more energy self-reliant cities. Its official energy self-sufficiency ratio exceeds 30%—well above the national average. However, that figure tells only part of the story.

The city’s impressive headline number is almost entirely driven by one district: Gijang-gun, located on Busan’s eastern edge, home to the country’s oldest and most powerful nuclear power complex. Gijang alone accounts for an energy self-sufficiency ratio of 1,990.6%, effectively exporting energy to the rest of the grid.

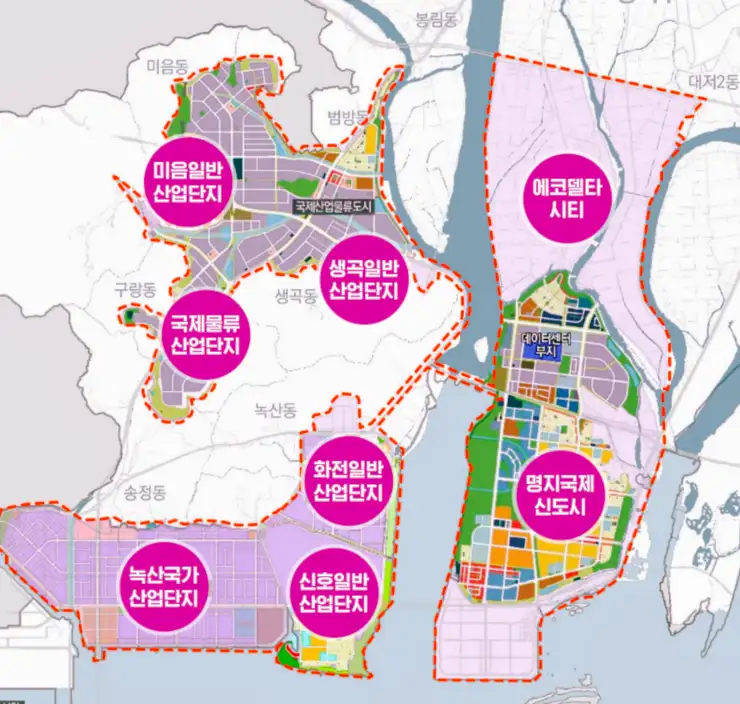

But outside of Gijang, the picture shifts dramatically. Twelve of Busan’s fifteen administrative districts generate less than 1% of the energy they consume. Even Gangseo District, home to industrial parks and the upcoming smart city of Eco Delta, produces just 7.1% of its required electricity. This imbalance is not just statistical—it is structural, with real implications for how and where energy-intensive businesses choose to locate.

The result is a paradox: while Busan appears energy-rich, most of its districts—especially in the west—remain critically dependent on centralized, vulnerable energy systems. Addressing this gap is not only a matter of energy policy, but a question of regional economic competitiveness.

A Legal Framework for Local Power

South Korea’s enactment of the Special Act on Activation of Distributed Energy in 2023 reflects a decisive policy shift toward restructuring the national energy system around more localized, resilient, and flexible sources of power. The law provides a legal basis for the designation of Distributed Energy Specialized Areas—specific zones where advanced technologies and regulatory exceptions can be piloted to accelerate the adoption of distributed energy.

Under the Act, distributed energy is defined as energy that is produced and consumed within the same or nearby location and falls within a prescribed scale. The legislation recognizes a diverse set of business types—including integrated energy, district electricity, renewable energy supply, energy storage, hydrogen, and demand response—as part of the distributed energy business ecosystem.

The framework categorizes Distributed Energy Specialized Areas according to regional characteristics and policy needs. In areas with high energy consumption, the goal is to ensure stable, localized supply. In resource-rich regions, the aim is to harness renewables for grid integration. A third category, iinto which Busan’s Gangseo District has been provisionally categorized, pending final designation, focuses on "new industry development"—an approach emphasizing energy-based business innovation.

These zones function as testbeds for emerging models such as Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), Virtual Net Metering (VNM), Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) as a Service, and AI-enabled demand management. In this model, energy is no longer viewed as merely a utility but as a strategic economic resource—one that can be traded, subscribed to, and used to catalyze regional competitiveness.

By applying for and being selected under this legal designation, Busan is not just seeking to improve supply reliability in Gangseo; it is leveraging the legal and regulatory flexibility granted under the Act to create a next-generation energy innovation zone, aligned with national goals for decarbonization, grid stability, and industrial advancement.

Storage as Strategy

At the heart of Busan’s strategy in the Gangseo Distributed Energy Specialized Area lies a single, yet transformative idea: store power locally, and use it intelligently. The planned Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) facility is not just an infrastructure project—it is a blueprint for how electricity can serve as a strategic asset in urban industrial policy.

Unlike traditional on-site storage, which typically serves a single building or factory, the Gangseo BESS is designed as a centralized, off-site storage platform. It will operate under a shared usage model, allowing multiple industrial users to access stored energy virtually through Virtual Net Metering (VNM). This means that even without physical proximity to the batteries, businesses in the district will be able to benefit from more affordable, stabilized power.

The facility will be rolled out in two phases: 250 megawatt-hours (MWh) of capacity is scheduled for installation by 2027, with a planned expansion to 500 MWh by 2030. It will utilize Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) batteries, a chemistry favored for its thermal stability and safety profile, aligning with Korea’s heightened ESS safety standards.

But energy storage is just the foundation. The project also incorporates artificial intelligence for load forecasting, enabling the system to predict usage patterns and dispatch power efficiently during high-demand periods. Furthermore, the city intends to offer UPS-as-a-Service to critical infrastructure—such as data centers, port facilities, and logistics hubs—ensuring power continuity without requiring each user to invest in redundant systems.

According to preliminary estimates by Busan officials, these services could generate up to ₩20 billion in annual electricity cost savings, though detailed cost-benefit projections have not been made publicly available. Yet beyond cost, the real value lies in the precedent: a shared, intelligent, and service-oriented energy system that positions Gangseo not just as a consumer of power—but as a manager and innovator of it.

What Busan Stands to Gain

The selection of Gangseo District as a finalist for Korea’s first Distributed Energy Specialized Area marks a potential shift in how Busan seeks to secure its industrial future—not only by ensuring energy stability, but by reimagining electricity as a tool for regional competitiveness.

One of the clearest anticipated benefits is cost reduction for power-intensive industries. With the Gangseo Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) in place, factories and logistics firms will be able to avoid peak-hour pricing by drawing power from storage during high-tariff periods. According to city estimates, this could result in electricity savings of up to ₩20 billion per year. In a district defined by high energy demand and low self-sufficiency, such efficiency gains could translate directly into enhanced business viability.

Yet the project is not solely about saving money. At a broader level, Gangseo's energy redesign introduces a service-based model of power delivery. By offering Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) as a Service, the city is making advanced reliability solutions available to businesses without the need for upfront investment. This has particular significance for emerging sectors like data centers, where power quality and continuity are mission-critical.

There are also implications for energy governance. Through tools like Virtual Net Metering, Gangseo’s model allows for more dynamic and decentralized energy transactions. Businesses are no longer passive consumers; they can participate in energy arbitrage, storage leasing, and real-time load balancing. This aligns with national goals to move toward demand-side management and local energy autonomy, as outlined in Korea’s Special Act on Activation of Distributed Energy.

Ultimately, Gangseo stands to gain more than just reliable power. If successful, this zone could serve as a national pilot for how industrial cities transition toward distributed, intelligent energy models—where cost, carbon, and control are optimized through infrastructure that is both physical and digital.

The Uncertainties Ahead

While the Gangseo Distributed Energy project has drawn attention as a bold model of local energy innovation, its future success remains contingent on overcoming a range of technical, institutional, and behavioral uncertainties.

First, there are operational risks inherent in large-scale energy storage infrastructure. Although the use of Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) batteries reflects a conscious move toward safer chemistries, Korea’s track record with ESS fire incidents has left a residue of caution. Ensuring long-term stability will require not only robust system design but also a strict safety management regime—something that remains to be stress-tested at the proposed scale.

Second, the economic assumptions behind the project—particularly projections of ₩20 billion in annual savings—are dependent on adoption rates among local businesses. While large firms may be ready to engage in services like virtual net metering or UPS subscriptions, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) may be more hesitant, lacking both familiarity and internal capacity. This raises questions about whether the shared energy model can truly scale without targeted outreach, education, or incentives.

Third, there are regulatory mismatches to consider. While the Special Act on Activation of Distributed Energy provides a legal framework for experimentation, much of Korea’s broader energy market remains built around centralized grid operations. Whether distributed models like Gangseo can operate smoothly within existing tariff systems, transmission rules, and market settlement procedures is still unclear.

There is also the question of equity and governance. If energy infrastructure becomes a monetized service, who benefits most? Without inclusive planning, there is a risk that such zones could amplify disparities between capital-rich firms and smaller actors. Public trust will depend on the city’s ability to ensure transparency, fair access, and community oversight throughout deployment.

In the end, the uncertainties facing Gangseo are not flaws—they are the defining characteristics of a pioneering policy experiment. But they demand continued attention, adaptive governance, and above all, accountability for outcomes that go beyond technical performance to include public value.

Not Just Energy, but Leverage

Gangseo’s candidacy as a Distributed Energy Specialized Area does more than showcase Busan’s energy strategy supply gaps. It signals a deeper transformation in how cities position energy—not merely as a commodity to be consumed, but as a lever to shape economic direction, industrial structure, and civic resilience.

By anchoring its strategy in large-scale energy storage, digital management systems, and shared service models, Busan is venturing into a new paradigm of urban energy governance. If successful, the initiative could serve as a blueprint for other cities seeking to decentralize power, reduce peak dependency, and align energy supply with local industrial policy.

But this future is still being written. From battery safety to market integration, from equity concerns to business adoption, the Gangseo project embodies all the complexities of an experimental zone. Whether it becomes a national benchmark or a cautionary tale will depend not only on technology or budgets—but on transparent governance, adaptive learning, and sustained stakeholder commitment.

What is clear, however, is that Busan is no longer waiting for energy to be delivered. It is beginning to design, govern, and leverage it—on its own terms, for its own future.

As of May 2025, Busan’s Gangseo District remains a finalist under review by the national Energy Committee. Final designation as a Distributed Energy Specialized Area is pending.

Comments ()