Can Busan’s Glocal Universities Deliver Real Change?

Glocal University 30 promised transformation, but for many institutions, it has become a race to survive — with proposals crafted faster than change can take root.

Busan, South Korea — In May 2025, South Korea’s Ministry of Education announced the final round of preliminary selections for its Glocal University 30 initiative — a flagship national project launched in 2023 to revive regional higher education institutions amid declining student populations and structural decline. Designed to designate 30 institutions over three years, the program has already begun channeling multi-year funding into earlier cohorts. The 2025 selections mark the last chance for universities to enter the program.

Among the 18 projects chosen for this final round, three came from Busan: a solo proposal by Kyungsung University, another by Busan University of Foreign Studies (BUFS), and a joint “1 National, 1 Maritime University” model led by Korea Maritime and Ocean University (KMOU) and Mokpo Maritime University. The Busan Metropolitan Government hailed the announcement as a milestone, signaling progress in its efforts to link higher education with local innovation and economic growth.

But beneath the celebratory tone of the city’s official statement, deeper questions emerge.

Do these universities possess the institutional capacity and academic credibility to realize their ambitious proposals? Or are these strategies, filled with buzzwords like K-Culture, AI education, and smart port ecosystems, more reflective of survival instincts than sustainable innovation?

Critics argue that the Glocal initiative — while bold in intention — risks becoming yet another short-term government program aimed at propping up institutions already struggling with enrollment and relevance, particularly in the private sector. Others point to the absence of stronger, research-focused national universities from the list, raising concerns about how selections were made.

As Glocal University 30 enters its final designation phase, the real test begins. The question is no longer simply who made the list — but whether they are truly equipped to lead meaningful transformation, or merely repackaging themselves to remain afloat.

Glocal University 30: Reform or Lifeline for Failing Institutions?

Amid growing alarm over the state of regional higher education in South Korea, the Ministry of Education launched the Glocal University 30 initiative in 2023 as a central pillar of its national education reform strategy. Now in its third and final year of selection, the program was designed to identify and support up to 30 universities capable of reinventing themselves as regional innovation hubs with a global outlook — a vision rooted in both educational reform and regional economic survival.

The initiative responds to a systemic crisis: a steep decline in university-age population, worsening financial instability among non-metropolitan institutions, and a persistent gap in academic competitiveness between Seoul and the rest of the country. Over 40 percent of universities — most of them outside the capital region — have failed to meet enrollment quotas in recent years, pushing many, especially smaller private institutions, to the brink of closure or forced consolidation.

Under the Glocal framework, selected universities are expected to propose comprehensive transformation plans — not merely rebranding or program updates, but structural overhauls that integrate academic innovation with regional industry, identity, and long-term strategic relevance. In exchange, they receive multi-year government funding, external consulting support, and elevated national visibility.

As of 2025, twenty universities have already been fully designated and are receiving support. The latest selections, announced this May, represent the final cohort — the last opportunity for institutions to secure inclusion. For these late-stage applicants, the stakes are particularly high. In Busan, three universities — two private and one public in a joint model — have been granted preliminary designation. Whether they ultimately succeed will depend not only on how much funding they receive, but on whether they can demonstrate the structural readiness, academic capacity, and institutional vision that true transformation demands.

Busan’s Glocal Contenders: Ambitious Proposals, Uncertain Foundations

Busan’s inclusion in the final round of the Glocal University 30 initiative has been framed by city officials as a pivotal opportunity to redefine higher education in the region. Three proposals were granted preliminary designation: Kyungsung University, Busan University of Foreign Studies (BUFS), and a joint initiative between Korea Maritime and Ocean University (KMOU) and Mokpo Maritime University. As these institutions prepare their final implementation plans for submission, scrutiny is intensifying over whether their stated ambitions can realistically be matched by institutional capability.

Kyungsung University, a mid-sized private institution in southern Busan, is proposing a transformation into a high-tech cultural production campus under the label “MEGA” — shorthand for Media, Entertainment, Gala/MICE, and Arts. The university envisions immersive media labs, a university-run content production unit, and a restructuring of its academic organization to form a consolidated “MEGA College” spanning more than half of its departments.

While the vision mirrors national policy interest in cultural exports, its feasibility remains uncertain. Kyungsung has little track record in high-level content production, and no clear infrastructure, personnel pipeline, or market alignment has been articulated. Critics note that without proven partnerships or implementation capacity, the proposal risks being seen as aspirational branding rather than a viable transformation model.

BUFS takes a different angle, positioning itself as a global data and language intelligence hub. Building on its foreign language credentials, the university aims to standardize multilingual education across dozens of institutions and develop AI-driven translation systems and market-specific language solutions to support regional industries with global reach.

The concept is bold, but the leap into AI and big data raises questions of technical readiness. While BUFS is respected in linguistics and interpretation, its profile in applied data science is minimal. Executing this transformation would require a research infrastructure and workforce it currently lacks, alongside significant cooperation from industries that have yet to publicly endorse the vision.

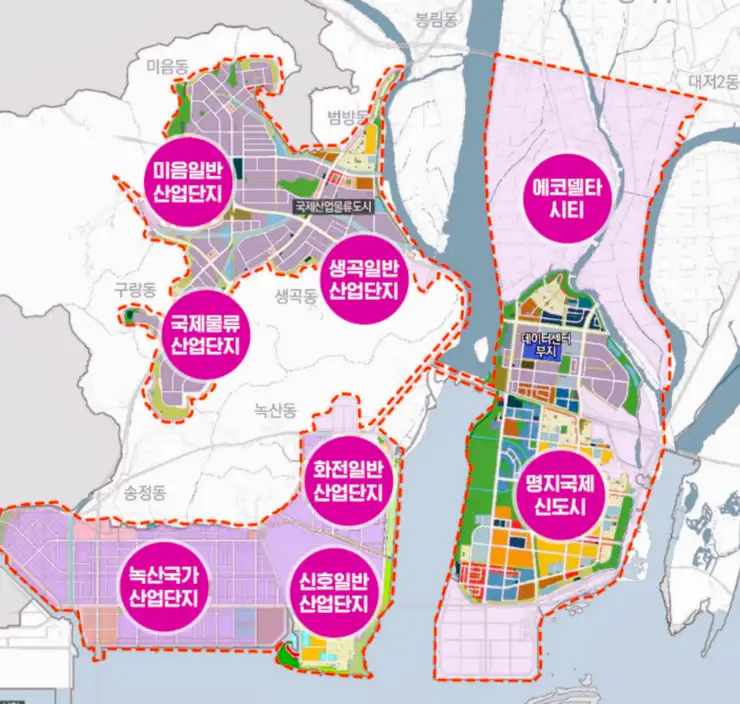

The most structurally ambitious of the three is the maritime university integration model. KMOU and Mokpo Maritime University propose to merge into a single, national maritime institution — a multi-campus entity underpinning Korea’s ocean economy. Their proposal emphasizes smart port technologies, autonomous navigation, and eco-friendly marine engineering — all areas in which Busan seeks to position itself as a global hub.

Still, institutional mergers in South Korea remain politically fraught and operationally complex, especially across provincial jurisdictions. Beyond legal and administrative integration, concerns linger about actual demand: can the maritime sector sustain the envisioned talent pipeline, or will this create duplication in a shrinking job market already affected by automation and decarbonization?

Taken together, Busan’s three Glocal proposals are bold in rhetoric but varied in depth. Each is navigating a tension between ambition and capacity, vision and execution. As the Ministry of Education prepares for final evaluations this fall, these institutions will need to prove they are more than policy beneficiaries — they must show they are equipped, in structure and substance, to drive the kind of transformation the program was meant to achieve.

Between Vision and Reality: Implementation Gaps and Structural Limitations

While the Glocal University 30 initiative is built on forward-looking ambitions, the widening gap between vision and execution has become a defining concern — particularly in Busan. With the final round of preliminary designees now tasked with submitting detailed implementation plans by August 2025, scrutiny is shifting from selection to feasibility. Whether the bold concepts outlined on paper can translate into operational reality remains an open and pressing question.

At the heart of the challenge lies capacity — both institutional and structural. For many participating universities, especially private institutions like Kyungsung and BUFS, the imperative to present transformative agendas comes atop long-standing vulnerabilities: chronic underfunding, declining enrollment, an aging academic workforce, and limited international reach. These are deep-rooted issues that cannot be resolved through rebranding exercises or acronym-driven frameworks alone.

Moreover, the structure of the program delegates much of the responsibility for transformation to the universities themselves. While the Ministry of Education provides financial resources and consultative guidance, it is the institutions that must oversee implementation — hiring domain experts, reconfiguring governance, building new infrastructure, and aligning academic offerings with industrial demand. For institutions already operating in deficit, such an organizational pivot may prove aspirational rather than achievable.

In Busan, these structural pressures are compounded by a disconnect between proposed educational outputs and the local economic landscape. Kyungsung's plan to become a content production hub assumes an ecosystem of regional demand and talent absorption that has yet to materialize. Similarly, BUFS's vision of a multilingual data platform hinges on robust buy-in from industry actors who have not been clearly identified. Without substantive industry integration, these projects risk becoming conceptually novel but practically insular.

Even the most structurally ambitious of the three — the proposed integration of KMOU and Mokpo Maritime University — is fraught with logistical and political complexity. Cross-regional mergers remain rare and contentious in Korean higher education, and the proposed “1 Country, 1 Maritime University” model will face intense scrutiny not only from bureaucracies but from local stakeholders and faculty. If it falters, it could cast doubt on the broader viability of national-scale integration as a reform strategy.

Time, too, is working against these institutions. With only a few months between preliminary designation and final selection in September, the window for translating vision into executable strategy is narrow. Institutions are now being evaluated not just on what they imagine, but on how quickly and credibly they can operationalize that vision. In this environment, proposal-writing skills may outweigh demonstrated executional capacity — an imbalance that could undermine the program's core objective.

Ultimately, the success of Busan’s Glocal University projects — and of the initiative as a whole — may depend not on the scope of their ambition, but on their willingness and ability to confront institutional limits. Without a candid reckoning with what can realistically be achieved, Glocal University 30 risks becoming another well-meaning policy that overpromises on transformation while underdelivering in practice.

From Grand Visions to Grounded Realities

As the Glocal University 30 initiative enters its final round of selections, the program stands at a critical crossroads — not just in terms of which universities are chosen, but whether the underlying assumptions of the policy can withstand scrutiny.

Launched with the promise of nurturing “globally competitive regional universities,” the initiative has often substituted rhetoric for realism. From the start, many institutions rushed to submit highly stylized proposals, crafted by small internal teams under immense pressure, rather than grounded, institution-wide transformation plans. These concept papers — filled with talk of AI, K-Culture, and global branding — often bore little connection to the actual capacities or strategic direction of the universities involved.

Meanwhile, the program’s growing emphasis on institutional mergers — particularly among public universities — has sparked debate about whether consolidation has become an unstated prerequisite for selection. While mergers may offer administrative efficiency and scale, they also demand long-term structural harmonization, cultural integration, and shared vision — all of which are difficult to achieve within the program’s five-year funding window. In some cases, the process of merging may absorb more institutional energy than it creates.

More fundamentally, the program reveals a deep imbalance in Korea’s higher education ecosystem. Private regional universities, already struggling under the weight of demographic decline and financial strain, are effectively sidelined — asked to compete with publicly funded institutions under unequal conditions. This raises questions not just about fairness, but about strategic clarity: What kind of higher education landscape is the policy actually trying to shape?

The overlap — and at times confusion — between the Glocal initiative and the RISE (Regional Innovation System for Education) program adds to the uncertainty. For universities caught between these two large-scale frameworks, policy fatigue and duplication of effort are real risks. Worse still, institutions left out of both are facing accelerated marginalization, further entrenching regional inequality.

If the goal is to elevate regional universities in a sustainable and equitable manner, then a more deliberate, differentiated strategy is needed — one that acknowledges the need to support, transform, and gradually phase out institutions based on their missions, strengths, and roles. Not all universities must be saved; but those with clear social value, even if modest in size, should not be erased by blunt competition metrics alone.

At this stage, success for Glocal University 30 will not be measured by how many buzzwords appear in planning documents, but by whether the selected universities can deliver enduring academic, social, and regional value. That will require more than funding and slogans. It will require honest evaluation, time, and a willingness to ask not just which universities survive — but which should, and why.

Comments ()